Tags

Bede, Ceadmon's Hymn, Criticism, Metal, Orality, Performativity

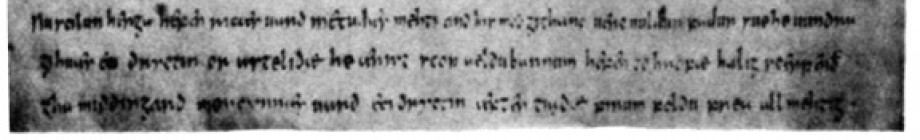

1. Depiction of Ceadmon

“Cædmon’s Hymn” is seen as the oldest surviving work of English vernacular poetry. Found in the margins of Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, It has long been a source of investigation by the academic community. This text offers a snapshot of cultural transition as older pagan oral poetic styles are reappropriated to suit a now Christian nation. This has lead to the work being dissected and analysed as a poetic text in every form of ‘scientific’ literary study style one can imagine(See Magennis, Kiernan and Shepherd for examples). All of these scientific styles wish to break down what survives in the hope of better understanding both the text and its context. However what survives today is unfairly cited as a poem when in fact it is a hymn. This causes us to approach the text with an inaccurate perception of its true performative nature.

The clue is in the title but this seems to be missed so frequently that its name is called into question through how the text is generally approached. Bede makes reference to the texts musicality, referring to it as a “song” and a “melodious verse” (Bede 418) in his accompanying prose passage but yet the need to deconstruct this work to fit critical poetic parameters persists. This ignores the nuance that defines “Cædmon’s Hymn” in its title as it is an oral piece designed to be sung. To ignore this text’s musical and performative qualities is to ignore its true effect on an audience and the reality of its oral origins. This limits our understanding of how the text works.

As there is no surviving musical notation we cannot reconstruct its melodies but we know that psychologically these melodies would have had a significant impact on the audience who heard them and would influence their reception of the hymn. Michael Thaut states that “music in the human brain creates and experiences a unique, highly complex, time-ordered, and integrated process of perception and action based on sensory events, as well as complex perceptual, cognitive and affective operations” (39). This gives music the power to evoke reactionary emotions and sentiments localised in its performers and audience’s cultural and emotional space. In this way melody and rhythm stimulate the three mnemonic modes of memory (reminding, reminiscing and recognising) unlike any other form of expression (Martin 23).

Melody and rhythm have the power to enforce cultural identity in ways poetry cannot. They offer “a sonic projection of territory” (Biddle 14) and construct “an image of singularity and permanence” (Martin 39) through culturally significant elements which offer a sense of identity through aural recognition and/or pleasure. The use of any earlier pagan style or variation of it would have a significant impact on the reception of the work. Within these elements of the performance we are faced with more factors which could alter the audience’s interpretation of the piece such as the use of cadences and rests, rhythm and instrumental accompaniment which all have the possibility to alter an audience’s understanding of the works message. These factors are not considered when “Cædmon’s Hymn” is read simply as a poem. The use of a major or minor key alone has the potential to change the performance from an optimistic rejoice at the power of God to an atonement for a pagan past. The style in which a song is performed alters ones understanding of it. As we only have the lyrics and no accompanying music, the possible alterations this may offer are ignored when they are in fact limitless.

2. Cover Art created for my version of “Caedmon’s Hymn

I have included an extreme example with this post in order to prove the power of music to suggest mood and alter ones interpretation of its subject. In the below example the combination of heavy metal with the poem’s religious content change its feel from what the text alone suggests. I am not suggesting that “Cædmon’s Hymn” included blast beats and a guitar solo. Instead I argue that the musicality of the piece has the potential to wildly alter the reception of the work and that because of this, musicality and performativity within “Cædmon’s Hymn” deserve more attention from the academic community.

Link to “Cædmon’s Hymn” lyrics.

(Note: This is only a rough example combining two existing works together to support an argument. This was never intended to be a serious musical work so I apologise for its poor quality. I took a brief section from “Nacreous” by Olympus Lenticular and a reading of the text sourced on YouTube and edited them slightly so they would flow better together. All credit goes to the individual performers who are cited fully below).

If enough interest is shown I am willing to record original songs in various genres using Old English lyrics to explore the various readings differing music styles offer.

Work Cited

Bede. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Eds. Bertram Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969. Print.

Biddle, Ian and Vanessa Knights. “Introduction.” Music, National Identity and the Politics of Location: Between the Global and the Local. Eds. Ian Biddle and Vanessa Knights. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 1-15. Print.

Martin, Denis. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. Cape Town: African Minds, 2013. Print.

Olympus Lenticular. “Nacreous.” Elucidate. Bandcamp, 2015. Web. 19 Oct. 2015. Mp3.

Thaut, Michael. Rhythm, Music, and the Brain: Scientific Foundations and Clinical Applications. New York: Routledge, 2005. Print

Illustrations

- Cædmon. University of Duisburg-Essen. uni-due.de. JPEG. Web. 19 Oct. 2015.

- Daly, James. Cædmon’s Hymn (Metal). 2015. SoundCloud.com. JPEG. Web. 19 Oct. 2015.