Tags

Boy Players, Performativity, Shakespeare, Textualities 16, Textuality, UCC English Seminar Series

Andrew Power’s seminar paper “Boy Actors in Shakespeare’s Early Plays” was very different from what I expected it to be. The field tends to focus on how boy actors have the ability to add multiple levels of reading to a renaissance performance through their ability to transgress gender and hierarchal boundaries on stage. Instead of doing what so many have done before, Andrew Power instead focused on the realities faced by boy actors, how they were trained within the theatre and developed as actors from apprentices to masters.

Andrew’s research focused very much on the textual nature of the plays as he had numerous charts detailing his laborious work in counting the amount of lines spoken by boy roles across all of Shakespeare’s works. He used this information to analyse their roles in relation to other roles played by veteran actors. As I am firmly in thesis research mode, I could not resist relating this to my current research. Andrew’s focus on these plays as set texts ignored the freedom in performance that drama and oral performance in general offers over textual works. Viewing Shakespeare’s texts as authoritive and final is not true as they were developed and altered to suit each performance, performer, venue and audience. Andrew’s study is based on the realities of the text as a blueprint for performance but ignores this basic reality of early modern theatre. Interpreting performative freedom is almost entirely speculative however, maintaining the necessity to understand the main prompt text in order to understand Shakespeare’s vision for each of these plays.

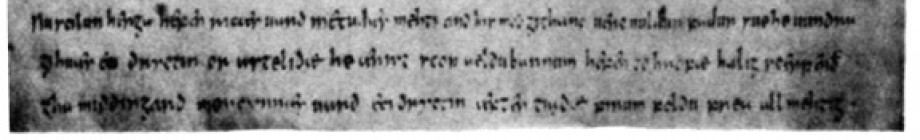

1. A modern interpretation of a boy player performing the role of a woman in John Ford’s The Lady’s Trial. (Photo by www.edwardsboys.org)

Boy players served as a symbol for the dangers of theatre among England’s anti-theatricalists who claimed that “the putting of women’s attire on men may kindle in unclean affections” (Rainolds 32) and lead to people playing “sodomites, or worse” (Smith 275). Anti-theatricalists favoured rigid, textual works that were of higher intellectual merit than these oral and theatrical performances. Books offered less potential for temptation and sin, instead offering teachings through the internal act of reading and meditating on the words as they appear on paper. This highlights the authorititve quality of textual culture over performance which has become a key part of my research into the interplay of orality and textuality in early English literature. This shows how this concept grew between the initial periods of English literature and renaissance English works.

This presentation charted the development of a boy player from a marginalised role with little lines into a Cleopatra or a Juliet. Marginalised female roles serving as both training positions for young actors while serving a function within the play is a very interesting idea that never occurred to me before and shows the reality of Shakespeare as a working playwright. It showed how actors could be and were trained in the oral element of their theatrical performance within an era of secondary orality. I have been focusing my research on an earlier pre-literate period. However it is true that Old English or Norse was never really pre-literate as runic inscriptions existed long before Latinate textual culture. As information on early English performance is sketchy at best while renaissance performance practices are well recorded and studied, the potential progression of this from Old English poetry through medieval English literature to renaissance theatre would make an interesting addition to my thesis or even a future project (potentially a PhD).

Andrew’s presentation clearly left its mark on my understanding of the realities of performance within renaissance England. The presentation itself had its shortcomings. Andrew read the entire presentation from a tablet with little engagement with the audience and one hand firmly in his pocket for the duration of the seminar. The presentation slides were dull and his charts were clustered and difficult to read from the back of the room. He was clearly showcasing his current research as a work in progress and in this way, it reminded me a lot of the early presentations I gave in the run up to Textualities 2016. I can relate to his position and need to further develop his presentation style as I faced a similar predicament a few weeks earlier. His content however was interesting and intellectually stimulating so I look forward to seeing how his ideas and presentation style grows.

Works Cited:

Power, Andrew. “Boy Actors in Shakespeare’s Early Plays.” University College Cork. Cork City, Cork. 9 Mar. 2016. Seminar Presentation.

Rainolds, John. The Overthrow of Stage Playes. Oxford: John Lichfield, 1599. Web. 10. Mar. 2016.

Smith, Bruce R., ed. Twelfth Night: Texts and Contexts. New York: Bedford St Martin’s, 2001. Print.

Illustrations